Lazy regulation: hospital price transparency

Don’t try to compare hospital prices; it’s hopeless

On 1 January 2021, a federal rule, 84 FR 65524, went into effect requiring hospitals to post documents disclosing their standard and negotiated prices.

In the explanatory part of the rule, the author, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, stated:

consumers want greater healthcare pricing transparency

we believe that transparency in healthcare pricing is critical to enabling patients to become active consumers so that they can lead the drive towards value

there is inconsistent (and many times nonexistent) availability of provider charge information

We believe this information gap can, in part, be filled by the new requirements we are finalizing in this final rule

The rule requires hospitals to post their standard and negotiated prices.

Massive noncompliance

One fact to note about this rule is that it is almost universally violated. The July 2021 Semi-Annual Hospital Price Transparency Compliance Report published by Patient Rights Advocate discloses an audit of 500 randomly selected hospitals and says:

We estimate that only 5.6% or 28 hospitals of the 500 randomly sampled, were in compliance with all of the rule requirements. We estimate that 94.4% or 472 of the 500 hospitals, were noncompliant ….

Useless compliance

Just as significant, however, is that even compliance with the rule does not do any practical good for informed patient healthcare shopping.

To see how impractical it is to use the disclosed data, let’s look at the first two compliant

hospitals listed in the Patient Rights Advocate report:

- Androscoggin Valley Hospital, in Berlin, New Hampshire

- Baptist Medical Center Jacksonville, in Jacksonville, Florida

The websites

Location

The rule requires hospitals to post their price data on a public website. They do that, but where? The rule says The standard charge information must be displayed in a prominent manner

, but does not say where on a website the data must be or how a user must be able to find the data.

On the Androscoggin website, you might expect them to be in the Health Tools

menu or the Services

menu, but they aren’t. Instead, you must use the About Us

menu or the Patients & Visitors

menu. There you must choose the Financial Services

link. But a glance at the destination page would tell you it’s the wrong page, because its headings are only about financial assistance

, until you get to the bottom of the page, where you finally reach a Cost Estimates

heading. However, a list of published prices is not a cost estimate, so you still seem to be in the wrong place. Only if you read the long paragraphs underneath it will you finally see the sentence, Androscoggin Valley Hospital's "Standard Charges," effective November 30, 2020, can be viewed by clicking here.

And what if you choose to search instead? If you search on the site for prices

, you get Your search did not return any results.

Billing & Insurance Information

link in the Patients

menu would get you there, but it doesn’t. Instead, and counterintuitively, you must choose the Cost Estimate Request

link. As with Androscoggin, that link name does not tell you that you can find published prices there. And, similarly to Androscoggin, the destination page seems wrong, because it is all about a tool for getting an estimate for an anticipated service—until you reach the middle of the page, where there is a Current Standard Charges

heading. Under that heading, you learn that Baptist publishes its prices, and you can click a Learn More

button. That opens a new page headed Gross Charges

, and on it is a link, Standard Charges for 10/1/20-9/30/21

. Searching for prices

is more productive on this site, because the Gross Charges

page is the 7th hit.

So, do these two compliant

hospitals post their data in a prominent manner

? My guess is that most users (and most judges and juries, if it came to that) would call the postings obscure

, not prominent

.

Accessibility

The rule says The hospital must ensure that the standard charge information is easily accessible, without barriers

, but does not expressly require the website to comply with current accessibility standards. This makes it unclear whether the website may violate these standards and thus discriminate against users with disabilities.

The Androscoggin website violates accessibility standards in several ways. One of the most obvious is that you can’t use its navigation menus with your keyboard (as blind or motor-limited users often do). Pressing the Tab key, you get lost, because the site deliberately prevents the browser from putting an outline around your currently focused menu button. And, even if you could see it, you could not enter its menu with the up-arrow, down-arrow, Enter, or Space key, which the standards prescribe as methods for opening and entering a menu.

The Baptist site comes closer to accessibility compliance, but it still contains violations. For example, its Get Started

link is defective, because it is too vague to let you know what it gets you started with, unless you can see the nearby text and infer that the link will get you started finding a doctor. If you were blind, you could not see the nearby text, and you might reach the link without ever hearing the nearby text from your screen reader.

The data

The rule requires hospitals to describe the services that they publish prices of. But it says little about

- Hospitals differ in how they format their data.

- Not every hospital describes the same service the same way.

- Not every description is intelligible.

A few examples will make these problems obvious.

Baptist lists the following service:

Antibody identification, RBC antibodies, each panel for each serum technique

Androscoggin does not list any service with that description, but does list this service:

AB ID RBC EA PANEL EA TECHN

They are, I am guessing, the same service. But I am guessing. The rule permits hospitals to make me guess. In addition, Androscoggin is abbreviating terms, without disclosing the meanings of the abbreviations. Accessibility standards require us to define our abbreviations, not leave their meanings secret.

The header of the Androscoggin description column is Name

. The header of the Baptist description column is /Facility/Charge/Item/Descr

. They are obviously different, and neither of them clearly tells you what is in its column.

The Androscoggin file contains only two columns, Name

and Amount

. The Baptist file contains 20 columns, all with confusing headers, such as /Facility/Charge/Item/DiscountCashCharge/#agg

.

/Facility/Charge/Item/Contracts/Contract/@Payer

, where it names various payers (such as CAPITAL HEALTH PLAN

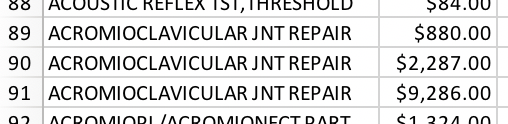

). But Androscoggin does not distinguish them at all. For example, it lists the service ACROMIOCLAVICULAR JNT REPAIR

three times, with prices ranging from $880 to $9,286, but says nothing to let you know which price might be relevant for you.

The Androscoggin file is in the xlsx (Excel) format. The Baptist file is in the csv (comma-separated values) format.

Both files of data require you to download them and open them locally. You cannot inspect them on the hospital websites. You cannot look up any price on either website.

Conclusions

If the judgments of Patient Rights Advocate are to be trusted, hospitals can comply with the current federal price-posting rules by:

- posting files of price data in places that are difficult to find

- forcing users to find the data by navigating inaccessible websites

- naming services as they wish

- naming services unintelligibly

- labeling columns of data incomprehensibly

- disclosing multiple prices with no explanation

- using diverse file formats

- forcing users to download and locally open files of data, instead of looking up prices on hospital websites

All these facts are bugs. They are deficiencies in the design of a user experience. They block users from convenient, intuitive access to information.

The Patient Rights Advocate report recommends that the rule be strengthened to require clear pricing data standards

. The organization made these specific recommendations for standards in a 25 May 2021 letter to the Department of Health and Human Services:

- a uniform file format, such as comma-separated values (CSV)

- full payer and plan names drawn from a standard list

- plan-specific (not only payer-specific) price disclosures

- a standard schema for the data

- access to the data through an application programming interface (API)

- standard billing codes

- anonymous user access to the data

- access to the data with one click from each hospital home page

- availability of the data as a file in addition to any interactive tool

Other features of a consumer-oriented standard might be:

- A standard navigation menu button labeled

Pricing

with standard menu items, linking directly to the data - Compliance by hospital websites with current digital accessibility standards throughout the flow of a user from the home page to the data.

- Standard, plain-language, unabbreviated descriptions of services

With such standards, all the things that people want to do with price data (except for obfuscating them) become easier and cheaper. Those include discovery, validation, aggregation, analysis, and explanation. Hospital A tells you you need procedure Blah. You can look it up in a health encyclopedia. You can compare its prices. You can determine which health-insurance plans would pay the largest shares of its cost. You can find out which hospitals perform it excessively and where patients who undergo it die.

Precise regulatory standards are normal. For example, the Americans with Disabilities Act Standards for Accessible Design do not fuzzily urge builders to avoid unreasonably steep

ramps. They specifically limit the slopes of a walking route to 1:20.

Given the formidable obstacles currently facing anybody who wants to make use of hospital-posted price data, it is astonishing and impressive that Patient Rights Advocate was willing and able to audit the data posted (or not posted) by 500 hospitals. But regulation designed to achieve the purpose of easily used information could make the job almost effortless. That kind of regulation is not armchair vagueness, such as in a prominent manner

or without barriers

. It is detailed technical specification, tested and revised for practical efficacy.

But lazy regulation, too, is normal. Powerful interests benefit from it. Therefore, reliance on regulation as the sole motivation for benign behavior is questionable. Patient Rights Advocate, when it collects information about hospital behaviors, also collects power, which it and others can use to influence those behaviors. Standards are typically defined and promoted by nongovernmental organizations, such as the International Organization for Standardization, and adopted by myriad entities that otherwise compete with one another. Those who want high-quality price-disclosure standardization by hospitals can win by leveraging such noncoercive organizing and not relying entirely on fragile regulatory force.